Enjoy this excerpt from our cookbook & cultural compendium More Than Borsch.

See more and buy a copy here.

Maslenitsa is a holiday that comes at the end of winter, meant to usher in the spring and celebrate the new warmth and coming bounty. In pagan times, the predecessor to Maslenitsa was Komoeditsa, celebrated the week before and the week after the spring equinox. Its celebration consisted of rituals with both a magical and religious bend, intermingled with merrymaking, games, feasts and riding on sleighs.

Tables were laden with cookies, pancakes and pies, oatmeal, honey, kvas and snacks. People in those pre-Christian times saw the hot, round, golden pancakes as a symbol of the sun, helping to warm the frozen earth, and by eating them, they, too, received a piece of its warmth. The circle was also a sacred figure, protecting people from evil.

Making pancakes was a huge part of this holiday. Perviy blin komam, it was said, as the first pancake was brought to a clearing as a sacrifice to the Bear god, the master of the forest. “The first pancake to the kom,” meaning ‘bear’ in old Russian, the sacred animal after which this holiday is named. The saying evolved: “The first pancake for the kom, the second for your friends, the third – your relatives, the fourth – for me.” We were always taught to say perviy blin komom, meaning that the first pancake always comes out lumpy, a sort of culinary life lesson. But in fact, it was always komam, “to the bears”, not komom, “as a lump”.

An important part of the holiday was the dramatic entry into the pagan temple of the straw figure of Marena, a mythological female figure, associated with changing seasons, the death and rebirth of nature. People stood along the road as she was carried through town, bowing to he and praising her.

A big campfire was lit, danced around and jumped over, all sorts of antics put on so that the spirits floating around wouldn’t recognize the revelers. Afterwards, they burned the effigy of Marena. Faces were washed with snow or snowmelt, for beauty.

Komoeditsa is full of rituals, such as Probudi, the Awakening. The bears were still asleep in their dens and it was time they woke. The people grabbed their burning torches and headed to a hole, where someone had disguised himself as a sleeping bear, hidden beneath fallen trees and leaves. They danced around it and sang, threw branches and handfuls of snow at the bear, but he wouldn’t wake until one of the girls sat on his back and hopped around, whereupon he would get up and begin to dance before heading off into the forest, singing a little bear song.

This holiday was imperative to enliven the people and give them strength and energy after a long, rough winter, to allow them some fun before the start of an arduous period of planting and harvesting.

From the 16th century, the pagan Komoeditsa began to fall on days during the Great Lent, which had specially been introduced to hasten its eradication, and during which merrymaking was strictly prohibited. “Cheese week” preceded the Great Lent, and it eventually turned into Maslenitsa. The name comes from maslo, butter or oil, in which blini, which play a central role in the holiday, are baked.

According to legend, Maslenitsa was the daughter of Moroz, frost, and lived in the north. One day, the small, delicate girl stumbled across a person; he saw her hiding behind the tall snowdrifts and asked her to help the people, who were tired from the long winter, to warm and cheer them. Maslenitsa agreed and turned into a solid, rosy-cheeked broad. Her deep laugh, dancing and blini made the people forget all about their winter troubles. A poem published in 1870 in the Satirical Gazette paints a portrait of her:

Here is the rosy-cheeked and stout goddess,

A heroine of feasting, drinking, fighting,

Reeling through towns, cities, villages…

But Maslenitsa wasn’t all fun and games. It was also necessary to prepare oneself for the long and exhausting fast to follow. Lent is strict: no meat, fish, dairy products or eggs, no parties, secular music, no dancing. All distractions from the spiritual life are forbidden.

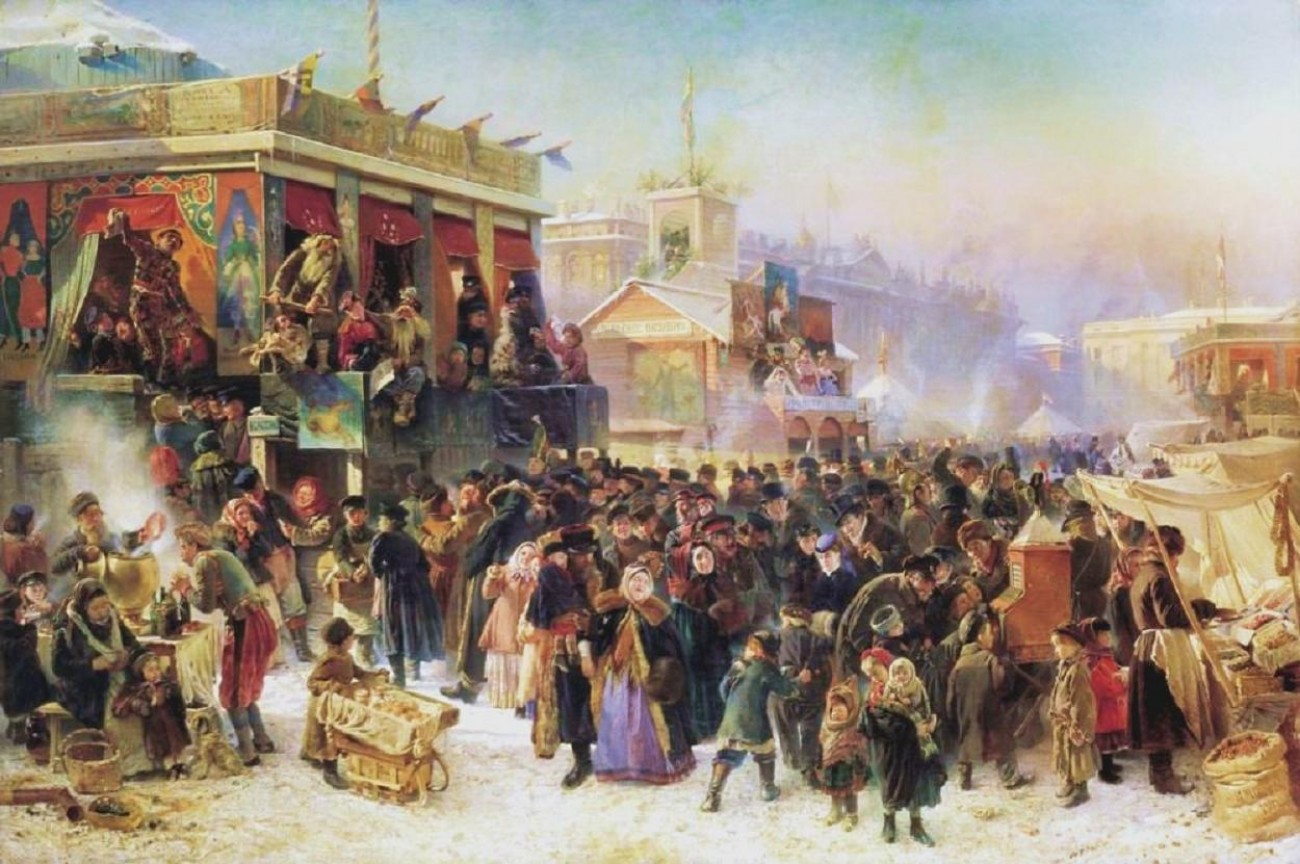

Despite being turned into a church holiday, this farewell to winter and welcoming of spring retained much of its folksy atmosphere and carried over many traditions from Komoedetsa. The celebration is noisy and festive; people ride troikas, carriages drawn by three horses, go sledding, hang out and go dancing, feast on beer and blini. During these days it’s no sin to “eat until you hiccup, drink until you change your mind, sing until you’re satisfied, dance until you fall.”

The blini remained, too. They were cooked in large quantities, used in almost every situal and given to friends and family all week, served with caviar, mushrooms jam, sour cream and of course, lots of butter. The Russian writer Aleksandr Kuprin described their uniqueness: “The blin is round, like the real, generous sun. The blin is red and hot, like the hot all-warming sun, the blin is covered in oil – this is in memory of the sacrifices, brought to the mighty stone idols. The blin is a symbol of the sun, red days, good harvests, successful marriages and healthy children.”

There is more baked on Maslenitsa than just blini, though: angel wings, cakes, cookies, various cottage cheese mixtures. In the southern regions of Russia and Ukraine, the holiday table is incomplete without vareniki, dumplings. In last place on the table is fish.

There is more baked on Maslenitsa than just blini, though: angel wings, cakes, cookies, various cottage cheese mixtures. In the southern regions of Russia and Ukraine, the holiday table is incomplete without vareniki, dumplings. In last place on the table is fish.

Every day of Maslenitsa had a different name and designation. Monday was vstrecha. People fetched their swings and their sleds, began baking blini. Tuesday was zaigryshi. In the morning, young people invited others to go sledding and eat blini. They told their friends and loved ones, “Our hills are ready, our blini are baked – please visit.” Wednesday was lakomki, a day when sons-in-law visited their mothers-in-law for blini. By Thursday, shyrokiy razgul, Maslenitsa was in full swing. People went ice-sledding, set up booths, swings, they rode horses, caravans, had fist fights and all sorts of noisy revelry. On Friday, teshiny vecherki, sons-in-law invited their mothers-in-law for blini, and on Saturday, zolovkini posidelki, young women invited their sisters-in-law. Newlywed women would also give their sisters-in-law a gift.

On Quinquagesima Sunday, after a series of rituals, the people burned an effigy of Maslenitsa, a stack of hay dressed in a shirt and a headscarf tied like a babushka’s. Into the fire, they threw all sorts of old things to symbolize the burial of the old and the worn.